The team from University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) are nearing the end of their assessment of the archaeological material from the Leicester Cathedral Revealed excavation and will soon have lots of new information to share. In the meantime, excavation director Mathew Morris, takes a moment to reflect on the anniversary of one of the most violent events in the Cathedral's history.

As I sit writing the assessment report, I am drawn to today's date, 31 May; 379 years ago today, during the first English Civil War, Leicester was attacked by the army of King Charles I. The siege and sacking of the town in 1645 played out over eight days – from its encirclement by Royalist troops on 28 and 29 May, to the artillery bombardment and call for the town's surrender on the 30th, and the final midnight assault on the defences and the capture of the town on the 31st, then the looting until the royal army departed on 4th June.

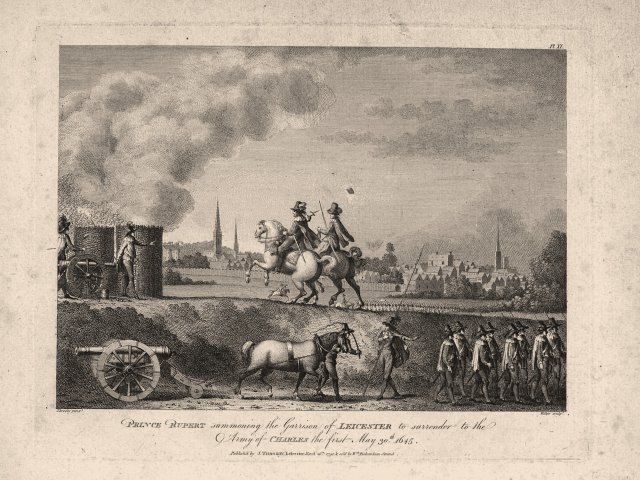

Image 1: Prince Rupert summoning the garrison of Leicester to surrender to the Army of King Charles the first – 30 May 1645. St Martin's is the church tower with the spire on the right of the image. Image: John Throsby (1790) / University of Leicester Special Collections

This was a brief but brutal chapter in the story of Leicester and the Church Warden's account books show that the parish church of St Martin was stuck in the middle of the fighting. Entries include a charge "for mending the locks of church doors, broken by the King's army" and for "laying down many graves which were taken up at the burying of divers great officers of the King's army, which was slain at the storming of this town". There is also a note that 30 shillings "was taken out of the poor men's box by the soldiers at the taking of Leicester."

The entries are frustratingly meagre. Why were the doors broken open? Was it to loot the church? Had civilians taken refuge inside? Or was it because its thick stone walls made it an ideal bastion for the garrison's last stand? Was their fighting in the graveyard? And where were the graves dug?

By accident or design, churches were often caught up in the fighting during the English Civil War. Their thick walls, lofty towers and walled graveyards gave them great military potential. At Leicester, St Margaret's Church and its graveyard were incorporated as a strong point in the town's outer defensive works. It was also the scene of fierce fighting during the siege and the town's governor Colonel Theophilus Grey, severely wounded, was captured in its graveyard. At St Mary de Castro too, crude Civil War era musket loops hacked through its medieval boundary wall can still be seen today. Whilst in the town's north suburb, on Woodgate, St Sunday's Church perished as a fiery prelude to the attack when the town's garrison burnt it down to prevent it being occupied by Royalist snipers.

St Martin's fate in the siege's aftermath was in stark contrast to events three years earlier when, as the pre-eminent church of the borough, it had hosted Charles I during his Royal progress to Leicester. Then there was pomp and pageantry not violence and death, flowers and sweet-scented herbs were spread over the church floor and there was a throne for the king, who had processed on foot through the streets from his residence at Lord's Place on the High Street (where Set and Toy Town are today) to attend the Sunday service. Accompanying him were the Mayor and Aldermen and the local militia, men who would all soon stand in opposition to him, with fateful consequences for the town.

Image 2: Charles I leaves Cavendish House, Leicester. Cavendish House mysteriously burnt down after the king's departure and can still be seen as a ruin in Abbey Park today. Image: Henry Reynolds Steer (1858–1928) / Leicester Museum & Art Gallery

It was an uneasy peace before the storm and four weeks later, on 22 August 1642, the King would raise his standard at Nottingham, declaring civil war against his people. Fast forward to the morning of 31 May 1645 and as dawn broke over Leicester, the King's 'blood guilt' was clear to see. With the defences breached the garrison retreated back through the town's narrow lanes. Fierce street battles and house to house fighting ensued, from the market place through the lanes around St Martin's to the High Cross (Jubilee Square today), as soldiers and townsfolk battled for their lives. Shots from windows killed Royalist soldiers, enraging their comrades "and many hundreds were put to the sword". Dead bodies lay in every street and it was said "that the honest women to preserve themselves from violence, did throw scalding water upon the soldiers of the King which was one cause they dealt so unmercifully with them" and "ere day fully opened scarce a cottage was unplundered."

Image 3: As the town fell, there was fierce fighting through the streets of Leicester as the garrison retreated to make a final stand at the High Cross. Image: Charles West Cope (1862) / UK Parliament

The entries in St Martin's account books are a reminder of the savagery of war, recording a church broken into and "miserably plundered" and a graveyard used for the burial of the war dead. Casualty figures vary wildly but over 700 people are believed to have died that night and were buried in Leicester's churchyards, including at least nine royalist officers buried at St Martin's; and this makes me wonder if we could find evidence of these events amongst our skeletons.

The likelihood of being able to successfully identify war dead from the Civil War is exceedingly remote but the stories skeletons can tell will add new depth to our understanding of the people of Leicester during this period, and it is remotely possible that one of those skeletons will show signs of battle injuries and a radiocarbon date will place their death in the 17th century and we might have evidence of that bloody night 379 years ago.

Image 4: An archaeologist excavates the remains of a wooden coffin at Leicester Cathedral. The biographically information picked out on the lid with brass upholstery studs reveals that this anonymous person was 56 when they died in 1641, a year before the outbreak of the Civil War. Image: ULAS

Mathew Morris MA ACIfA

Project Officer

Archaeological Services (ULAS)

University of Leicester