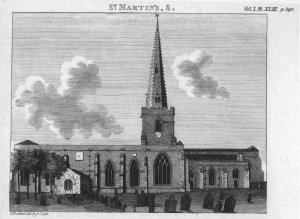

St Martin's church (Leicester Cathedral)

viewed from the south as it looked in

1792. The burial ground in front of the

church is full of gravestones although

the area we are excavating (right of the

tower) is mostly bare. Image: John Nichols

University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) have now been on site at Leicester Cathedral for a month.

Mathew Morris, the archaeology team leader for Leicester Cathedral Revealed, reveals what has been found so far…

This blog post focusses on the 19th century burial ground. A quick search online shows that around 17,500 people were buried at St Martin's (Leicester Cathedral) between the mid-16th century and the closure of the cemetery in 1856, with nearly 4,000 of those buried here in the first half of the 19th century alone.

This was a period when mortality was high, especially in towns like Leicester where rapid industrialisation, overcrowding, poverty and poor sanitary conditions meant it had one of the highest death-rates in Britain, exceeded only by Bristol, Liverpool and Manchester.

Old drawings and photographs show that the burial ground south of the church was originally full of tightly packed gravestones. Most of these have been moved or removed during various rearrangements of the Cathedral Gardens over the past 100 years and it was hoped that, when the Song School was built in the 1930s, the builders would have also cleared the more recent burials before construction began. This has proved not to be the case, however, and rows of 19th century graves are still present beneath the floor of the old building. Discovery of these graves has necessitated a phase of archaeological excavation much earlier than planned in order to carefully and sensitively remove the burials before they are accidentally damaged by the initial construction work.

The excavation so far has identified that the graves are laid out in neat burial rows which shows that a methodical burial system was taking place in the 19th century. At the time of writing ULAS have excavated 30 skeletons and expect this number to exceed 50 before this phase of work is completed. In the area south of St Dunstan's Chapel and east of the south aisle there are at least seven rows of graves laid out at right-angles to the cathedral. Most graves contain multiple burials, one above the other, most likely because they were family burial plots. This area of the church yard is also the closest place people buried outside the church could be to the altar and the area, therefore, would have been in high demand as a burial ground.

Two brick-lined graves. The upper

chambers of these graves were

both empty but both contain sealed

lower chambers which will be

excavated in the next phase of the

project in 2022. Image: ULAS

All of the burials so far are in coffins (more about the coffins in a later post) and are placed with their heads to the west. Most of the burials are earthfast, but scattered across the burial rows are a number of brick-lined vaults. These all have a similar design with brick walls mirroring the shape of the coffin. The bricks have been painted a cream or white colour creating a neat, sterile burial environment. At least six of the vaults have two tiers of burials separated by slate floors. In two of these multi-tiered vaults the upper chamber remained empty, presumably because they remained unused when the burial ground shut. Another vault had been reused to store charnel (loose human bone), presumably collected from the burial soil by grave diggers when they disturbed earlier burials.

One vault also contained a surprise. During the excavation it was discovered that it was backfilled with soil and many slate fragments. Initially we thought these were going to be the remains of the capping stones which had broken and dropped down into the vault but instead they turned out to be the smashed remains of a gravestone. We've put a little film together showing this discovery which can be viewed via YouTube.

The reassembled gravestone for

George Spencer and Charlotte Ross.

The inscription reads 'In affectionate

remembrance of George Spencer,

who departed this life, October 25th

1834; aged 42 years. Also of Charlotte,

wife of Thomas Ross, and niece of the

above who died April 21st 1831; Aged

22 years.' Image: ULAS

ULAS have also been able to trace the names on the gravestone. Trade directories indicate that George Spencer was a needle maker living on the High Street in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. His niece, Charlotte, the daughter of George's sister Jane, married Thomas Ross in 1829. Whilst Charlotte predeceased her uncle the gravestone appears to have been erected in George's memory with Charlotte's name added underneath. Unfortunately, we do not know where they were buried but it is unlikely to have been the brick-lined vault in which the stone was found as it only contained the remains of one individual.

Putting names to burials is very difficult, even when they are less than 200 years old. The next blog post will take a closer look at one person we have identified by name, so watch this space…