Over the past couple of months, we have been on site at the Cathedral intermittently monitoring the construction of the piling wall and other footings for the new visitor and learning centre. This work has given a tantalising preview of what might lie beneath the graveyard.

The archaeological investigation is largely paused at present whilst we wait for the current phase of groundwork to finish and give the space to start the next phase of excavation. In the meantime, there has been great interest from the BBC about what we have found so far, and there have been some new discoveries and hints of what might be to come.

There is very little we, as archaeologists, could do whilst the piling retaining wall was being installed. The piling rig is an enormous auger, 60cm in diameter, boring down ten metres into the ground. During the next phase of excavation, this piling wall will hold back the soil as the basement area is excavated, making it safe to work without undermining the surrounding buildings, and it will then form the wall of the basement itself and the foundation for the building above. As the auger is removed, each hole is immediately pumped full of concrete and a reinforcing steel cage is pushed in before it sets. During this process identifying archaeology and archaeological artefacts is very difficult, and we have mostly been recovering human remains from the displaced soil.

That said, we have also had a few insights into what might be beneath the burials. The dark cemetery soil is looking like it will be 1.5-2.5m thick. Beneath is a paler, sandier soil which has produced some large sherds of Roman pottery and a small quantity of building material, including roof tile and box flue (needed in buildings with hypocausts – Roman underfloor heating). In several places the auger has also hit tightly packed granite rubble about 3.5m below the ground. This might indicate that there are Roman wall footings still in place down there.

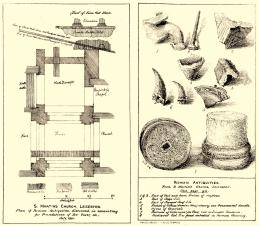

Our knowledge of this area of the Roman town is still very limited, largely due to the fact that this is the historic quarter of the present city, with few opportunities for archaeological excavation nearby. We do know that a Roman building was found beneath the Cathedral tower and north transept when they were rebuilt in 1861. The discovery was reported in the second volume of the Transactions of the Leicestershire Architectural and Archaeological Society in 1870.

"The excavations at S. Martin's, Leicester, have brought to light many antiquities of great interest. Several considerable portions of the foundations of ancient walls have been discovered: and, upon removing the earth in July last on the north side of the church close to the palisading dividing the church ground from the Townhall Lane, the workmen came to a rubble wall of considerable thickness, surmounted by a wrought stone platform, upon which stood the bases of two massive Doric columns, each about two feet in diameter. These columns, in all probability, formed a portion of a colonnade, which, judging from their size and the space intervening between about ten feet would be one of considerable length. The earth in the interior also contained numerous fragments of Roman pottery, and the bones of animals and birds. Two coins the one of Nero, the other of Constantine were likewise turned up; the truth of the tradition that a Roman temple stood upon the site of the present church being thus, it is presumed, unequivocably proved." (TLAHS 2, 90)

To say that this explicitly proved that there was a Roman temple beneath the Cathedral is a bit of a leap. In truth, the evidence could equally support a colonnade along a shop front, or the peristyle around a courtyard, or any number of other interpretations. This is what makes the new excavation so exciting. Here is a unique opportunity to see what this area of Roman Leicester was like.

Other groundwork, including the construction of a new ground beam close to the Cathedral, has revealed something of the original construction of the Cathedral's Great South Aisle. At the end of the trench for a new ground beam, where the below-ground masonry for the east wall of the south aisle was exposed, a complex story of building and rebuilding was uncovered. You can explore it in this 3D model.

As we see it today, the south aisle was rebuilt, or at least the stonework was re-faced, during John Pearson's restoration work in 1896-98 (find out more about the Cathedral's restoration here). This was after St Dunstan's Chapel was rebuilt from the foundations up during Raphael Brandon's restorations in 1865-67. Beneath the Victorian wall, however, is part of the original medieval wall and foundation. The original aisle is thought to have been built in the late 13th or early 14th century. The roughly coursed wall was bonded with orange sandy mortar and was built from a mixture of local granite and sandstone, and also incorporated some recycled Roman brick (similar to the walls of St Nicholas' Church next to the Jewry Wall). The medieval foundation used larger granite boulders bonded together with mud, and one of these foundation stones appears to be part of a recycled quern stone (used to grind grain into flour).

The original medieval wall and

foundation of the Great South Aisle.

The large circular block of stone in

the centre appears to be part of a

recycled quern stone. Image: ULAS

Already we are getting invaluable new information on the construction and past use of the building, information which will enable us to better tell the story of the Cathedral site and help the Cathedral better plan for the future maintenance of this important historic City building.

Mathew Morris MA ACIfA

Project Officer

Archaeological Services (ULAS)

University of Leicester