University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) are making good progress with the initial phase of archaeological excavation and investigation.

Mathew Morris, the archaeology team leader for Leicester Cathedral Revealed, tells us more about the first burial the archaeological team have identified by name.

An archaeologist carefully

excavates a name plate on a

coffined burial at Leicester

Cathedral. Image: ULAS

Putting names to the dead when they are skeletal remains is very difficult. The burials we have excavated so far are all late 18th and early 19th century in date, but even though they only died 150-250 years ago most will remain nameless. This is because the information we can gather from each skeleton – age, sex, stature, ancestry, diet, period of death etc. – is too broad to identify specific individuals. Even DNA analysis, if carried out, won't identify people by name, especially if they have no known relatives alive today and have multiple family members buried in the same cemetery.

This ambiguity can be frustrating but occasionally we are able to recognise enough unique characteristics to name specific burials. In the example I want to talk about in this blog post, it is because the name plate on the coffin was still legible.

So far, most of our burials are in wooden coffins which are adorned with name plates (also called depositum plates) fixed to the lid of the coffin. Unfortunately, most of these are made of die-stamped iron or tinplate (tin-dipped iron) and the writing is painted on the plate's surface.

Part of a nameplate with white-

painted writing on a background

of black paint. The metal and

paint is now too degraded to be

readable. Image: ULAS

After a century or more in the ground the thin metal has become corroded and brittle and has disintegrated into hundreds of small unsalvageable fragments.

There has been one exception. A grave close to the St Martins East passageway contained a person buried in a coffin with a brass plate which had writing etched on its surface – 'John Wilson Ottey, died 31st May 1851, aged 40'.

A preliminary search of the available records online finds Mr Ottey.

In the year of his death, the 1851 Census lists him as living on Town Hall Lane (Guildhall Lane today), just the other side of the Cathedral from where we are digging, with his wife Susanna (aged 29) and a 13-year old domestic servant named Amy Geary. His occupation was 'plumber and glazier'.

The same census records a second Ottey household in Leicester, one street over on the High Street, where Joseph Ottey (aged 67), John's father, lived with his two daughters, John's younger sisters Sarah Ottey (aged 35) and Mary Wootton (aged 32, a widow) as well as Mary's two children John and Mary (aged 13 and 11 respectively).

There was also a 17-year old house servant named Susanna Woodward.

John Wilson Ottey was born on Christmas Day 1810, to Joseph and Sarah, and was baptised two days later in Mary de Castro Church (the family appear to have been living in that parish at the time as John's parents married in Mary de Castro in 1808). The 1841 Census shows him living with his parents and his sisters on the High Street and an 1843 trade directory lists 'Ottey, Joseph and John, plumbers and glaziers, High St'. In 1844 John married Susanna Brightman from Ampthill in Bedfordshire, after which the couple presumably set up their own household in Town Hall Lane.

John and Susanna do not appear to have had children and Susanna outlived her husband by only a year, dying in 1852. Joseph died in 1856, leaving Sarah Ottey executor of her father's and her brother's wills.

The family business does not appear to have outlived Joseph's death. By 1861, Sarah had moved from the family home in the High Street to 10 Hastings Street (once part of a row of houses behind New Walk Museum, now long gone and beneath Waterloo Way) and was taking in borders. Her niece, Mary Wootton was also living with her.

We can continue to pick up the family in various census records. Sarah Ottey never married and by 1871 had moved away from Leicester to live with her sister in Islington. Mary Wootton was also living with her mother and her aunt. Mary's brother, John Wootton, became a travelling salesman in the hosiery industry.

The Coronation Buildings on

Leicester's High Street, built in

1902 and formerly the site of

No. 86 where the Ottey family

once lived. Image: Leicester Mercury

In 1881 all four were still living in Islington, John was described as a traveller (woollens) and Mary a school mistress. John and Mary's mother died sometime before 1891 when John was living with his sister and aunt in Hornsey in Middlesex.

Both Sarah and Mary are listed as wool workers whilst John is described as a traveller. They were still living together in 1901. Sarah Ottey was now 85 and she and Mary (now 52) were still listed as wool workers, working from home. Sarah died in 1904. John and Mary were still alive in 1911, both in their 70s, unmarried and living together in Hornsey. John was still a commercial traveller (clothing) whilst Mary was still a wool worker.

Identifying named individuals like John Ottey within the burial ground at St Martin's gives us a poignant and personal connection with our past. These rare discoveries also act as anchors, fixed points in time, which are invaluable when studying the burial assemblage as a whole.

The spatial relationship between John Ottey's grave and those around it will help us phase the cemetery and will aid our understanding of how it changed over time. It is also conceivable that it may help, in conjunction with surviving burial records, to identify other burials nearby.

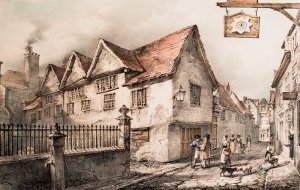

Townhall Lane (Guildhall Lane

today) c.1830, looking west.

Artwork: John Flower. Image:

Leicester Museums and Art Galleries

In my next blog, I'll be taking a closer look at some of the artefacts being found in the burial soil.

Mathew Morris MA ACIfA

Project Officer

Archaeological Services (ULAS)

University of Leicester | University Road | Leicester | LE1 7RH | UK

t: +44 (0)116 2522848

e: mlm9@leicester.ac.uk

w: www.le.ac.uk/ulas/