University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) are undertaking the archaeological excavation for Leicester Cathedral Revealed. In their latest blog, Dr Sarah Inskip from the University of Leicester, and Project Leader for the Tobacco Health and History project, explains what we hope to learn from the burials excavated during the project.

A skeleton,

contemplating a skull.

Photolithograph after

a woodcut by A.

Vesalius, 1543. Image:

Wellcome Collection

In our day to day lives we tend to forget about our skeletons. However, they are absolutely crucial for everything that we do; they protect our organs, allow us to move, they store crucial minerals and nutrients, and produce blood. Rather than being static, bone is very much a living dynamic tissue that is constantly remodelling and adapting to keep us healthy and functioning. This process is affected by many things, including the environment, our nutrition as well as the physical activities we do. This relationship means that the skeleton can be a valuable source of evidence about these factors and social processes that might influence them.

Osteoarchaeologists, or biological anthropologists, specialise in the detailed analysis of skeletal material (bones and teeth). They are trained to know every 'lump' or 'bump' in the skeletal system and to understand the normal and abnormal variation that can exist in human groups. They can also use biochemical approaches that allow them to look at the microstructure of bones and teeth which permit them to look in great detail about the lives of past people. Osteoarchaeologists can estimate sex, age, and height from the skeleton, as well as assess peoples' diseases, diet, mobility, and genetic past. By bringing the data of multiple individuals together it is possible to look at the characteristics of a population, and comparisons with other groups or overtime can show how key social factors have influenced our lives and wellbeing throughout our evolutionary history. This could be anything from how did farming change our relationship with infectious pathogens, how did industrialisation impact physical health, or how has climate change influenced nutrition. These questions can be addressed at multiple scales from international to local. The individuals excavated from the cathedral will allow us to look at how the lives of people changed over time as Leicester went from being a small town through to an industrialised city.

A researcher from the Tobacco,

Health and History project measuring

hand bones. (Images: Tobacco, Health

and History Project/UoL)

As part of the Tobacco, Health and History project, we hope to undertake a series of analyses that will reveal information about the lives of the inhabitants of Late Medieval and Post Medieval Leicester, a time of significant social and economic change. One of the aims of the project is to learn about the tobacco use practices of people from 1600-1900 and how this impacted on peoples' physical wellbeing.

We can tell whether people were using or were exposed to tobacco from their skeletons by using a combination of methods. The first is to simply look at the teeth of individuals to look for 'pipe notches'. These notches are caused by the habitual holding of clay tobacco pipes in the teeth, usually while doing manual work. The clay pipe stems abrade the enamel away leaving a distinctive circular hole. We can sometimes also see tobacco staining on teeth. As not all types of tobacco use was with a pipe, the project has developed a method (metabolomics based) to assess for chemical signatures that relate to tobacco use in bone and teeth. This is the first time that we will get a direct and detailed picture of tobacco use practices within pre-20th century groups.

Left: Teeth of an individual with a

clear round hole caused by holding

a clay pipe. Right: Lingual staining

on inner surfaces of teeth from using

a tobacco pipe. Images: Tobacco,

Health and History Project/UoL

Once we know whether people were using tobacco, we can then compare this to what diseases we see on the skeleton. In particular, we are looking for evidence of respiratory diseases, oral pathologies, nutritional diseases, cancers and neoplasms. Already Don Walker and Michael Henderson (2010) has shown correlations between respiratory health and tobacco use in London and it would be interesting to see if the same pattern emerges in Leicester.

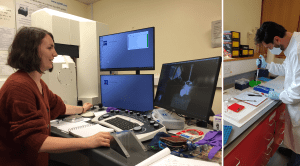

Researchers from the Tobacco,

Health and History project using

a scanning electron microscope

to explore microwear on teeth

caused by clay pipe use (left)

and preparing bone samples for

analysis of small molecules

relating to tobacco use (right).

Images: Tobacco, Health and

History Project/UoL

At the same time as assessing tobacco use and disease, we will also be assessing what sort of things Leicester people ate through their bone chemistry (stable isotope analysis), what other diseases and traumas they suffered from (perhaps through work or their living environment), how long did they live for and how tall they were. In conjunction with historical sources on life in Leicester, and of some that pertain directly to excavated individuals (e.g. censuses, Wills etc), we will be able to reconstruct Leicester life stories, or osteobiographies, an approach which builds up a picture of someone's life using as many types of information as possible. This approach was used on Richard III, but is arguably far more valuable when applied to individuals for which we have limited historical information, especially the urban working classes. Through this, we hope to reveal the lives of individuals from all walks of life from Leicester and to further our knowledge about its diverse community. We will compare this to other places, including London and Barton-upon-Humber to help show the unique situation of Leicester, and how life here compared with other places. This will help build up a more complex picture of life during the post medieval period in England, which saw huge disparities in wealth, core industries, lifestyles and health.