University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) are undertaking the archaeological excavation for Leicester Cathedral Revealed. In his latest blog, archaeology site director Mathew Morris presents some fascinating research on John Wilson Ottey - the first burial the archaeological team were able to identify by name during the initial phase of archaeological excavation and investigation. Mathew's research discovered that John Ottey was involved in a tragic incident when he was a young man, resulting in him being charged with manslaughter.

BREAKING NEWS (well, 185 years ago!). We have an update about Leicester Cathedral Revealed's first named individual, John Wilson Ottey. Site director Mathew Morris previously wrote about John Ottey last November and further research in newspaper archives has brought to light a tragic incident when he was a young man. The Leicestershire Mercury reported events on its front page on Saturday June 24, 1837 under the headline 'Manslaughter at Leicester'…

"On Monday afternoon an inquest was held at the Haunch of Venison, High-Street, on view of the body of William Townley, whose death was occasioned by Thomas Bonnett and John Ottey giving him a considerable quantity of ardent spirits."

William Townley was 12 years old, the son of William and Lydia Townley, a retail hosier on the High Street.

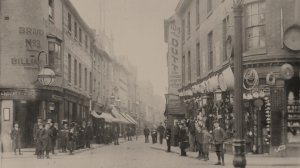

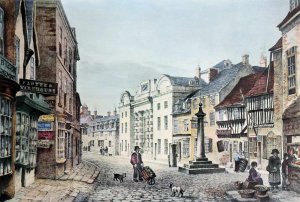

Leicester's High Street in the late

19th century, about 30 years after

the events of this story. Looking east

from Highcross Street. Image: ROLLR

The newspaper details the tragic events and the ensuing inquest. The main witness, Thomas Ward (16), of the Rose and Crown Yard, Crab Street (St Marks Street today, off Belgrave Gate), described what happened:

"I was in Free-school Lane, on Tuesday evening [June 13], about eight o'clock, with Edward and Charles Chamberlain and William Townley; we were playing near Mr Bonnett's gate, and young Mr Bonnett came out and asked me to set up some pins [nine-pins or skittles]; none of them went in but me, and Mr Bonnett asked me why two or three more had not come in; and I said they would not; in a short time Mr Bonnett opened the gate and called some of the other boys, but they did not come; in a few minutes afterwards William Townley and Charles Chamberlain asked me to let them in, and I did; Mr Bonnett then said "set some pins up lads;" there were Mr John Ottey there and Mr Thomas Bonnett, and another young gentleman [Mr Edmund Seymour Palmer] whose name I did not know."

"After they had been playing about half-an-hour, Mr Bonnett brought a jug containing nearly a pint and a half of gin and water; he gave me the jug, and said "Here, drink;" I drank a little and gave it to William Townley, and after he had drank he gave it to Charles Chamberlain, who also drank; it was not very strong; Charles Chamberlain was going to take it to the top of the yard, when Mr Bonnett, who was at the top of the yard, said "Come, drink again;" then he brought it down again and gave it to William Townley, and we all drank again; then Mr B came down just as I had got it in my hand, and said "Come, make haste, for there are ten more jugs to come in;" I finished it and gave the jug to Mr Bonnett, soon afterwards he brought down the same jug nearly full of rum and water and gave it to me in my hand, and told me to drink; the other two young gentlemen were playing all the while, and we were still setting up the pins; we all three drank out of the jug, and then Charles Chamberlain put it on the ground; all the gentlemen drank; we played a good while before we drank again, and then they sent one of us to fetch it; I did not drink then, and Chamberlain and Townley emptied it; then Mr Bonnett fetched some more gin and water in the same jug; after they [the players] had drank Mr Bonnett brought it to us, and we all drank again; it was about three parts full when it was brought to us; then after we had drank Charles Chamberlain began to tumble about, and in about five minutes afterwards, whilst he was setting up pins, William Townley fell down; then I set some pins up by myself, while both of them were rolling about; then the young gentleman, whose name I do not know, brought me down the jug and said "Come, drink! You do all the work yourself," but I told him I did not want; Mr Bonnett saw the two boys tumbling about, and he said "Come, come, let's have none of this;" the three gentlemen were all sober; young Mr Ottey then came down to Mr Bonnett and said "I'll bet you a penny that this boy [meaning the witness] drinks whats in the jug," and he said if I did drink it I should have the penny, but I told him I would not try; they all three went to the top of the yard, where they bowled from, and stood laughing at the two boys who were tumbling down and getting up again; then Mr Bonnett came down and said "Come, you must go home," and he opened the gate; they got out by holding the gate, but they soon tumbled down, and I fell down too; my father was outside, and, after I had fetched my whip which I had left behind me, he took me home; I saw young Townley lying on the ground in the yard when I went to get my whip."

"My father led me home; I was very sick and ill when I got home; I ate my breakfast as usual in the morning, but I had a very bad head-ache."

Charles Chamberlain (9), of Free-School Lane, corroborated most of Thomas Ward's account, although he insisted that he hadn't voluntarily entered the yard, Thomas Bonnet had pushed him in, and that it was John Ottey who was passing around the jug of alcohol, not Bonnett. He also insisted that John Ottey had forced him to drink out of the third jug by holding it to his mouth. The inquest attributed the discrepancies in the two accounts to the witnesses' drunken state.

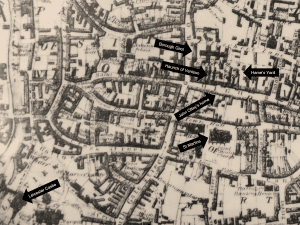

Extract from Burton's 1844 map of

Leicester showing the main locations

relating to the case. Image: ROLLR

Lydia Townley, William's distraught mother, detailed what happened next:

"I had not seen my son since dinner-time on Tuesday, but my mother, who lives with me, said that he came home [from school] about five o'clock and had a piece of bread and butter; he seemed quite as well as usual at dinner time; his constitution was delicate, but he had tolerably good health; about eight o'clock my eldest girl told me he was lying in Hame's-yard [accessed from the High Street, approximately where Shires Lane is today], and I found him quite insensible; while I was undressing him he said "Bonnett did it," two or three times, and then after that he fell asleep, but he did not awake for twelve or fourteen hours; I gave him a teaspoonful of ipecacuanha wine* but it did not operate till some medicine was sent from Mr Paget's; I should think that he vomited about a pint; I thought when he was lying on the ground that he was playing tricks, and I gave him two or three slaps on the back; he was twelve years old last March; the room smelt very bad of spirits indeed; and what came up looked and smelt like rum."

*also known as ipecac, a medicinal syrup used as an expectorant and diaphoretic and, in high doses, an emetic. The Leicester Chronicle recorded that Mr Paget's assistant saw the boy at ten o'clock on Tuesday evening and administered an emetic powder.

Thomas Paget, the attending surgeon, concluded the narrative:

"I saw the deceased between five and six o'clock on Wednesday morning [June 14] having been from home the previous evening, and he was then completely insensible, but was reported to have recently moved his arms, as if recovering from a state of still greater insensibility; from that time he gradually recovered from his inanimate state, and became subject to delirium at intervals; from ten o'clock strong inflammatory symptoms set in, of which he died this morning [June 19] about two o'clock."

'The Tree', 99 Highcross

Street, formerly the Haunch

of Venison, the public house

where the inquest was held.

Following Townley's demise, his father charged John Ottey (24) and Thomas Bonnett (19) with being the cause of his son's death and they were immediately taken into custody and an inquest was convened. Thomas Paget carried out the autopsy, assisted by the surgeon William Hitchcock on behalf of the young men. Paget reported:

"I have just opened the body in conjunction with Mr Hitchcock, and find inflammation to be seated in the stomach and lungs, which the latter organ exhibited appearances of previous severe disease; the inflammation of the stomach and lungs I consider to be quite sufficient to cause death; the previous disease of his lungs rendered him more prone to violent disease, and enfeebled his frame so as to render him less able to bear it; it may be proper to notice that, ere long, the diseased state of his lungs would most probably have caused his death; there was nothing to point out the cause of the inflammation of the stomach, but the drinking of ardent spirits of sufficient strength or in sufficient quantity to produce insensibility would probably cause inflammation of the stomach, and if he had drank spirits to excess, I have no hesitation in saying that was the cause of his death."

Hitchcock concurred with Paget's conclusions, although as a witness for the defence he placed greater emphasis on the fact that the disease in the lungs "would have ultimately caused his death" and that there were other possible causes, other than alcohol, for the inflammation of the stomach and the lungs. Regardless, it took the jury less than thirty minutes of deliberation to return the verdict:

"That the deceased died from having an inordinate quantity of ardent spirits incautiously administered by John Ottey and Thomas Bonnett, but not with the intention of destroying life."

The coroner, John Gregory, asked the jury to clarify that their verdict was manslaughter, to which the foreman replied "Yes sir, it amounts to that; but we wished to convey it in terms as little painful as possible to the parties implicated."

View of the Borough Gaol on Highcross

Street, where Ottey and Bonnett would

have been incarcerated. Image: John

Flower, 1830

With this, the accused were committed to take their trial at the summer assizes, which commenced on Saturday July 29 (6 weeks later) in the new Assizes Court in the Great Hall of Leicester Castle, with the Honourable Justices Sir James Parks and Sir William Bolland presiding. Sixteen prisoners were to appear before the borough court – two charged with breaking and entering, ten with theft, one with assault and three with manslaughter. Nine cases were heard that Saturday with the remainder, including Ottey and Bonnett's, postponed to the following week.

On Wednesday 2 August, Ottey and Bonnett were tried before Mr Justice Park. No new evidence was submitted by the prosecution and in summing up, Sir James Parks determined that the charge of manslaughter could not be sustained and directed the jury to acquit the prisoners. He had a stern sermon for the two young men, however:

"I would lay aside the office of judge, in which character I consider that I have done my duty to you and to the country, and I would speak to you as a man and a Christian. I am glad that the case has terminated in the manner it has, as I did not think that you intended any harm to the boy who has unfortunately lost his life, and I should have been sorry to have seen you convicted of the offence with which you were charged, after the evidence of the very respectable surgeon who stated that there were symptoms of disease as left no doubt in his mind that ere long the boy must have died; but still I would have you understand that I considered that you were guilty of a very horrible offence, as there could be no doubt that you hurried the boy into the presence of his Maker, by your wonton folly and wickedness. I was sorry to see two respectable young men placed in such a disgraceful situation, and I hope that your narrow escape will be a warning to you, and not only induce you to refrain from drunkenness yourselves but to discountenance it in others, and by earnest prayer night and day for the forgiveness of your sin, make some atonement to the afflicted parents for the loss of their child."

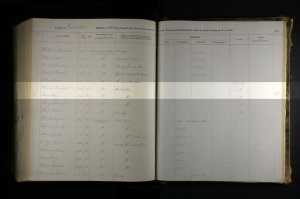

A page from the 'Register of all Persons

charged with Indicatable Offences at the

Assizes and Sessions held with the County

[of Leicester] during the Year 1837'

showing the acquittal of John Ottey and

Thomas Bonnett. Image: National Archive

So, relief for John Ottey and Thomas Bonnet – had they been found guilty they could have faced up to life imprisonment – but little consolation for William Townley's grieving family.

William Townley's death was the tragic consequence of excessive alcohol consumption by a group of young people, in which pressure to drink was applied by the older members of the group. The story is sadly very relatable today. Bonnett's and Ottey's actions were irresponsible and stupid, they had made the younger boys drink to get them drunk and had then made fun of their drunkenness with no regard for the consequences, but there was no intent to cause harm. Access to the alcohol was probably made easier because Bonnett lived with his elder brother Henry, a wine and spirit merchant. However, the witness Thomas Ward's recognition that the alcohol was watered down suggests that he was used to drinking spirits and hints at a pervasive drinking culture in the town's younger generations. Townley's death, therefore, was a terrible accident that the young men could not have foreseen, with the alcohol exacerbating the boy's terminal lung disease and hastening his inevitable death. This, sadly, did not make it any less senseless.

We don't know how the event affected John Ottey and Thomas Bonnett. Did they take their brief imprisonment and the judge's sermon to heart? The 1830s was a period of emerging temperance in Britain and the first Temperance Society in Leicester had formed the previous year.

We don't know how quickly society forgave them either. This was not the first time Bonnett had fallen foul of the law. Only two months earlier he had appeared before the Magistrates accused of firing a gun in his brother's backyard, breaking a neighbour's window. Was this to be a recurring theme of delinquent behaviour? There are no further records of troublemaking but Bonnet's own life was cut tragically short by consumption (tuberculosis) 14 months later, he was only 21 years old.

There are also no other records of John Ottey. He joined his father's business as a plumber and glazier and the Leicester Chronicle described him as 'much respected' when they reported his own untimely death, fourteen years later. Clearly some youthful transgressions could be absolved.

Mathew Morris MA ACIfA

Project Officer

Archaeological Services (ULAS)

University of Leicester