Following the Christmas break, University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) have been back on site for a couple of weeks and have now completed Phase 1 of the archaeological excavation and investigation, with a total of 124 burials excavated. Ground works have now started, including installation of a contiguous piled wall that will define the basement of the new visitor and learning centre extension. Within this, further archaeological excavation and investigation can be then be safely undertaken and ULAS will be back in the spring for Phase 2.

Mathew Morris, the archaeology team leader for Leicester Cathedral Revealed, recently gave a very interesting and well received online talk about the Phase 1 archaeology work.

The talk was recorded and is now available to view on the ULAS YouTube channel.

In his latest blog below, Mathew tells us about our second named individual, Anne Barratt, whose grave was uncovered during Phase 1.

The brick-lined grave

and wooden coffin of

Anne Barratt. Her

grave was dug through

an earlier burial, a

testament to how

crowded the burial

ground was in the 19th

century. Image: ULAS

Everyone in Leicester has a connection with Richard III, people have grown up being told stories about him, watched his reburial, visited his tomb in the Cathedral or parked on his grave. But how does this relate to our project? Well, Anne Barratt also had a connection with the king, although we don't know if she knew about the link herself.

Before Christmas we excavated the last brick-lined in our area of work. These are exactly what they sound like, a brick burial chamber built to house a coffin. Some are multi-tiered and were intended as family vaults. Others are single chambers and the added expense of constructing a brick-lined vault for the burial is usually taken as evidence of the wealth and aspirations of the deceased's family. We have excavated ten altogether, scattered amongst the mid-19th century burial rows.

Anne Barratt was buried in a brick-lined grave close to the south aisle. Her coffin-shaped vault was sealed with slate and sandstone capping stones. Inside, the brickwork was rendered with white paint giving it a clean, clinical appearance and the coffin was exceptionally well preserved with a brass nameplate on the lid inscribed 'ANNE BARRATT, BORN 23RD NOVEMBER 1786, DIED 16TH NOVEMBER 1855'.

The brass nameplate on Anne

Barratt's coffin. The simple

rectangular plaque is engraved

'ANNE BARRATT, BORN 23RD

NOVEMBER 1786, DIED 16TH

NOVEMBER 1855'. Image: ULAS

Our research reveals that Anne was the youngest of eight children of John and Jane Barratt. John Barratt (b.1740) was a wealthy Leicester hosier – hosiery was Leicester's staple industry. He married Jane Andrew in 1771 and that same year he bought a fine new townhouse on Friar Lane, spending a total of £1,150 on the property. The house still stands today, at 17 Friar Lane, and is considered 'the handsomest Georgian house now left in the town'.

Its garden, now a rather famous car park, stretched north towards St Martin's covering the area where Richard III's remains were uncovered in 2012, and the Barratt children would have grown up playing over the king's grave. Were they aware that this was the site of Richard III's burial? We don't know and by the 18th century the story was widespread that the king's body had been dug up thrown into the River Soar. It's a connection nevertheless and demonstrates how interconnected we are with our past.

The Barratt's first child, named John, was born in 1773, followed by Joseph (b.1774), Jane (b.1775), Thomas (b.1777), Mary (b.1779), Sarah (b.1781), Elizabeth (b.1784) and finally Anne (b.1786). All eight children were baptised in St Martin's church. So far, we have found very few records for the three eldest and it is probable that they died young leaving Thomas heir to his father's hosiery business. A Leicester trade directory of 1815 lists Barratt & Son trading from Friar Lane, with Thomas Barratt, hosier, living in Humberstone Gate with a warehouse in Friar Lane.

The three older surviving siblings, Thomas, Mary and Sarah, all married but the two younger sisters, Elizabeth and Anne, never wed. What Anne did for much of her life remains a mystery. Surviving records describe her as a 'landholder' and a 'gentlewoman', meaning she was independently wealthy and of good social standing. In her Will she left legacies to the Leicester Infirmary and to the 'Society in Leicester for the relief of the poor' whilst contemporary newspapers periodically mention her subscriptions to local charitable causes, including in 1836 the construction of a new church, Christ Church, on Bow Street in Leicester and its school for poor children.

Christ Church, Bow Street, Leicester.

In 1836 Anne Barratt donated £10

towards its construction (about £600

today). Construction was completed

in 1839, it was demolished in 1957.

Image: ROLLR

Whilst Anne's parents were alive, they undoubtedly provided financial support for their unmarried daughter. By today's standards, the Barratt's were millionaires. John Barratt was a successful businessman with property as well as stock in both the Ellesmere and the Union canals. Anne's mother died in 1824 (aged 78) and her father (aged 85) died the following year. In his Will, John left Anne over £4000 (at least £300,000 today), ensuring her future financial independence. Thomas inherited his father's property and business, including 17 Friar Lane, whilst Anne's other sisters received similar cash legacies. Anne continued living at Friar Lane.

Anne's sister Elizabeth died in 1835 (aged 50) and Thomas died in 1839 (aged 62). Both were buried at St Martin's and both are remembered on memorials in St Dunstan's chapel, as are their parents. Thomas bequeathed 17 Friar Lane to his daughter Mary Jane, who lived there with her husband, the Rev. Richard Fawsett (rector of Christ Church, the church Anne had helped to finance), until they moved to Smeeton Westerby in 1852. Subsequently, the house was leased to a Dr Benfield who eventually purchased the property in 1866.

The Grey Friars in 1865, whilst

Mary Burnaby was still in residence.

Anne spent her last year's living

here with her sister. Image:

greyfriarsheritage.org.uk

We don't have another reference of Anne until 1851, when the census records her living with her sister Mary. Mary had married a Leicester attorney called Beaumont Burnaby Esq in 1798. In 1824, Burnaby bought The Grey Friars, the house next door to the Barratt family home. The Grey Friars was built by the prosperous Leicester alderman Robert Herrick in the late 16th century on the site of the medieval Franciscan friary (where Richard III was originally buried). Subsequent owners enlarged the house until it was the largest private residence in Leicester. Following Beaumont Burnaby's death in 1848 it passed to Mary. Under Mary's ownership the house was divided in two, with Mary living in the larger, western part until her death in 1885.

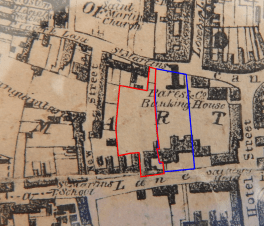

A detail from Burton's 1844

Leicester town plan, showing

17 Friar Lane (red) and The Grey

Friars (blue), the two properties

most associated with Anne

Barratt. Image: ROLLR

In 1851, Mary was living at The Grey Friars with Anne, supported by five servants – a footman, a cook, two housemaids and a kitchen maid. Anne passed away four years later. She was 68. Her death certificate records that she died at home of 'chronic disease of the stomach with ulceration'. Her niece, Mary Jane Fawsett was with her when she died.

Anne was buried shortly after November 16, 1855. Her wooden coffin was covered with red or black coloured fabric which was held in place by rows of decorative coffin studs. Other metalwork included eight decorative grip plates with handles, fixed three to a side and at either end, whilst the engraved brass nameplate was fixed to the flat lid.

The head end of Anne Barratt's

coffin was remarkably well

preserved. In this image the

cloth covering, rows of decorative

coffins studs and one of the grip

plates and handle can be seen.

Image: ULAS

The coffin was double-shelled (one coffin inside another), an added expense, and was lined inside with padded fabric. Little of Anne's body remained but she was probably laid out in a shift-like shroud and she was wearing woollen stockings – the storyteller in me would like to say that they were made by her family's hosiery business but I don't know that for certain! Her burial ensemble was finished off with a frilled cloth wrapped around her head and she was wearing earrings.

Top: the frilled cloth wrapped

around Anne Barratt's head.

Left: A detail of one of Anne

Barratt's woollen stockings.

Right: One of Anne Barratt's

earrings with a faceted stone.

Images: ULAS

She remained a wealthy woman, as revealed by the bequests and legacies set out in her will. Anne left all of her household goods, furniture, plate and linens to her sister Mary; her clothes and jewellery to her niece Eleanor Dabbs (daughter of her sister Sarah); a gold watch to her nephew William Dabbs; and her mother's gold watch to his brother John Dabbs. She also left cash legacies for her great-nephew John Barrett Fawsett and niece Mary Elizabeth Fawsett, and her god-daughter Agnes Susan Nedham; as well as money for her servant, Elizabeth Huges.

Anne Barratt was one of the last people to be buried in the graveyard at St Martin's, which shut the following year. By the mid-19th century, the town's burial grounds were overcrowded and considered a health hazard. The town council, enabled by the Leicester Burial Act in 1848, had opened Welford Road Cemetery in 1849 and subsequently prohibited interments in the town's other churchyards and burial grounds which had all effectively shut by 1855.

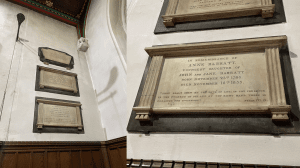

Photo 9. Anne Barratt's memorial

in St Dunstan's Chapel in Leicester

Cathedral. The memorials above

hers are to her sister Elizabeth,

and to her parents and her sister

Jane. Images: ULAS

Today, we found Anne's grave, unmarked by any gravestone, lost beneath the floor of the Old Song School since the 1930s. She is not forgotten, however. When the Cathedral reopens, visit St Dunstan's Chapel and look at the memorials on the wall to the left of the altar. Anne's is there, beneath memorials to her sister Elizabeth, and her parents and her sister Jane. Look behind you and you will also find a memorial to her brother Thomas on the opposite wall. A Leicester family, still remembered together in a place of worship which must have been so integral to their lives.

COMING SOON: A blog about coffins, an update on the life of John Wilson Ottey and a first look at what analysis of the skeletons will tell us about the people of Leicester.

Mathew Morris MA ACIfA

Project Officer

Archaeological Services (ULAS)

University of Leicester