At present University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) are waiting to resume their excavation at Leicester Cathedral. Work hasn't stopped, however, and over the past couple of months they have been on site as needed monitoring groundwork for the installation of the piled basement wall for the new visitor and learning centre. Work is also progressing behind the scenes and the examination of the first burials has started - a closer look at the work of the analysis team will be covered in a future update.

Meanwhile, archaeology site director Mathew Morris has been promising a blog post on coffins and here it is…

The people of Leicester have been burying their dead in coffins for over 1,800 years. In the town's Roman cemeteries nearly half of the burials were in wooden coffins and discoveries of lead coffins are described in antiquarian reports. Wooden coffins were also used in the medieval period, although they weren't as common (none were found during the excavation of St Michael's church and only 3% of the burials at St Peter's church were in coffins). Lead coffins and stone sarcophagi were rarely used, although examples have been excavated in the town, most recently at the church of the Grey Friars.

These early coffins, usually only identifiable by regularly spaced iron nails framing a burial, were rectangular or trapezoidal. Construction was simple, with the end and side boards nailed or pegged to a single base board to create a flat-lidded box.

The archaeology of coffins. Top: An exceptionally well preserved Roman coffin from Great Holme Street (1976). The rectangular wooden box was constructed from planks held together with wooden pegs. Bottom left: The shape of a trapezoidal medieval wooden coffin at St Peter's Church (2005) is still clearly visible because of a layer of ash spread across the bottom of the coffin. The ash may have been a symbol of repentance and humility, or may have been to counter foul odours and soak up fluids. Bottom right: A medieval stone sarcophagus with an inner lead casket buried beneath the sanctuary of the church of the Grey Friars (2013). It contained the remains of a high status lady, probably a benefactor of the friary. Images: ULAS

In most instances, people in the Roman and medieval town were shrouded or wrapped in a winding sheet before burial, with use of a coffin an indicator of more elevated status than burial without. Following the Reformation in England in the 16th century, however, and the abolishment of the doctrine of Purgatory, commemoration and remembrance moved away from the need to pray for the dead and focused more on the deceased and what they were buried in. By the end of the 17th century, use of coffins was more universal and decorating their exterior became increasingly important in conveying individuality and status.

Towards the end of the 16th century a new coffin shape became popular. Called a singlebreak coffin, it was widest at the shoulders and tapered towards the head and feet (the classic 'coffin' shape). From the 17th century, the flat-lidded single-break coffin was the standard form. It's not clear why this more complex shape was favoured over a simple rectangular box but, as it is only used in funerary contexts, it may have been adopted as a distinctive container by a burgeoning commercial funeral industry.

An archaeologist excavates a

burial at Leicester Cathedral.

Whilst the coffin wood doesn't

survive, the coffin shape is still

visible in the soil. The

rust-coloured ovals are the backs

of the coffin handles. Image: ULAS

So far, our burials at Leicester Cathedral have all been from the 18th and 19th centuries, with the earliest dating from 1738 and the most recent 1855. All were buried in single-break coffins and we have already noticed a number of distinct styles. Wood doesn't survive well in Leicester's soils and only a few samples have been recovered from some of the brick-lined graves. These have yet to be examined but coffins were traditionally made of elm, although oak or more exotic woods were also used and pine was often a cheaper substitute. The wooden boards were typically butt-jointed and fixed together with glue and/or nails and wooden pegs, and we have noticed that whilst some of our burials did contain coffin nails, others didn't despite there being other obvious signs that a coffin was present (e.g. coffin handles), suggesting glue or other carpentry techniques were being used.

Top: an archaeologist excavates

the remains of a coffin lid decorated

with brass coffin studs. Bottom: The

finished excavation. Whilst much of

the coffin lid was missing, three

lines of letters and numbers were

still partially visible. The bottom

number is probably the date of death,

'[1]738'. Images: ULAS.

Undertakers were usually carpenters, cabinetmakers or upholsterers by trade, who did undertaking as a side-line. Our earliest coffins reflect this, with the external decoration and writing picked out with dome-headed brass upholstery tacks. This practice first developed in the late 17th century and was primarily used to secure a fabric cover to the coffin's exterior with single or double rows of tacks creating framed panels around the coffin handles (called grips in the trade). Sometimes the tacks were also used to spell out the initials, age and year of death on the coffin lid.

By the mid-18th century, cast and die-stamped metal coffin fittings were increasingly available and affordable and largely replaced the use of coffin studs to convey information. Coffin embellishments included a name plate (also called a depositum plate or breast plate), other decorative lid motifs and escutcheons for side decoration, grips (handles) and decorative grip plates.

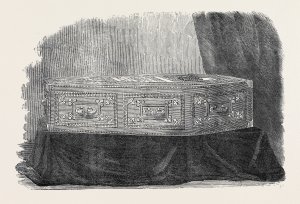

A Victorian coffin decorated with

coffin studs, a nameplate, lid motifs,

escutcheons on the sides, and

decorative grips and grip plates.

Many of our late 18th and 19th

century burials have coffin furniture

like this. Most coffins had a name

plate, usually made of iron although

we have had two examples in brass.

More elaborate coffins were covered

with a felt-like fabric fixed down with

coffin studs or coffin 'lace' (bands of

tin-dipped stamped iron in assorted

decorative patterns, for outlining the

lid, sides, and ends of a coffin). Some

were augmented with other lid motifs.

By the early 19th century, Birmingham had become the main centre of coffin furniture production in Britain, with undertakers ordering from trade catalogues and pattern books. One of our coffins had grips stamped with the mark of Edward Lingard, a Birmingham manufacturer in the early 19th century.

Top: Double rows of dome-headed

brass coffin studs decorating the side

and lid of a coffin. Bottom: Coffin 'lace',

a band of decorative stamped metal

imitating coffin stud decoration.

Image: ULAS.

The cost of coffin furniture varied depending on the material used and the finish. Most of the fittings from our cemetery are the less-expensive tin-dipped iron (called 'white' in the trade) or black-painted iron. Unfortunately, this does not survive well in the ground and is usually in too poor a condition to lift intact. Personal information was also painted on the name plates rather than engraved and does not survive, meaning most of our burials will remain nameless.

The exception has been two engraved rectangular brass nameplates, which survive better. Patterns were often hard to decipher through the corrosion but the name plates were usually shield-shaped or oval and surrounded by classical embellishments of drapery and vines, or other foliage. Some may have incorporated winged cherub's heads or angels with trumpets and included a crown at the top.

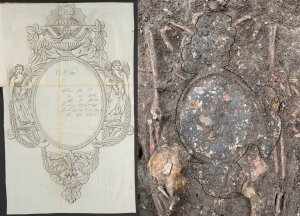

Left: A nameplate in a coffin furniture

pattern book from 1823. Right: The

same large nameplate (it was 60cm

long) found covering a burial at

Leicester Cathedral. The central oval

was painted black with writing in red

paint for 'MARY GREENWOOD, DIED

4TH MARCH 1810, AGED 29'. Images:

Yale Centre for British Art & ULAS

Looking through 18th and 19th century coffin furniture pattern books, we can see that there was a lot of choice, which could be mixed and matched to personal taste. Coffin grips and their decorative backing plates are a good example of this, coming in many shapes and sizes. Most adult-sized coffins had eight grips, three to each side and one at each end, whilst smaller coffins typically had six.

Some of coffin handles from Leicester

Cathedral, ranging in style from small

and simple to large and ornate.

Image: ULAS.

This variation can be seen best in two contemporary coffins from adjacent brick-lined graves close to the south aisle of the cathedral. One was for Anne Barratt, who I've previously written about, the other for an Elizabeth Sturgess. Both died in 1855, Anne was 68, Elizabeth was 74. Anne's coffin was very well preserved. It was covered with red coloured fabric which was held in place by rows of decorative iron coffin tacks, painted black. Other metalwork included eight decorative grip plates with handles, also painted black, whilst the nameplate was a simple engraved brass plate.

In contrast, Elizabeth's coffin, whilst poorly preserved, showed no evidence of having a cloth cover (no coffin tacks or coffin 'lace') and it was adorned with tin-dipped iron furniture, including a name plate, two additional decorative lid motifs and eight grip plates with handles. The writing on the nameplate was painted in gold and white on a black background.

The rectangular brass nameplate on

Anne Barratt's coffin (left) and the

more decorative tin-dipped iron

nameplate on Elizabeth Sturgess's

coffin (right). Images: ULAS

The variety, quantity and quality of these fittings was probably predicated on the taste, wealth and aspirations of the deceased's family. As we excavate more of the burial ground, the Leicester Cathedral Revealed project will give us a fascinating insight into the changing use and style of coffins in Leicester, and the history of the town's funerary trade. Previous excavations in the city have examined medieval cemeteries and 19th century cemeteries but for the first time this project will enable us to examine a continuous burial sequence from the early medieval period through to the mid-19th century, giving us a unique opportunity to chart how coffins and burial practices have evolved over the past 1,000 years.

Mathew Morris MA ACIfA

Project Officer

Archaeological Services (ULAS)

University of Leicester